Our Work in Elaine, AR

Commemorating the Victims of the Elaine Massacre

(Trigger Warning: Images of Racial Violence/Murder)

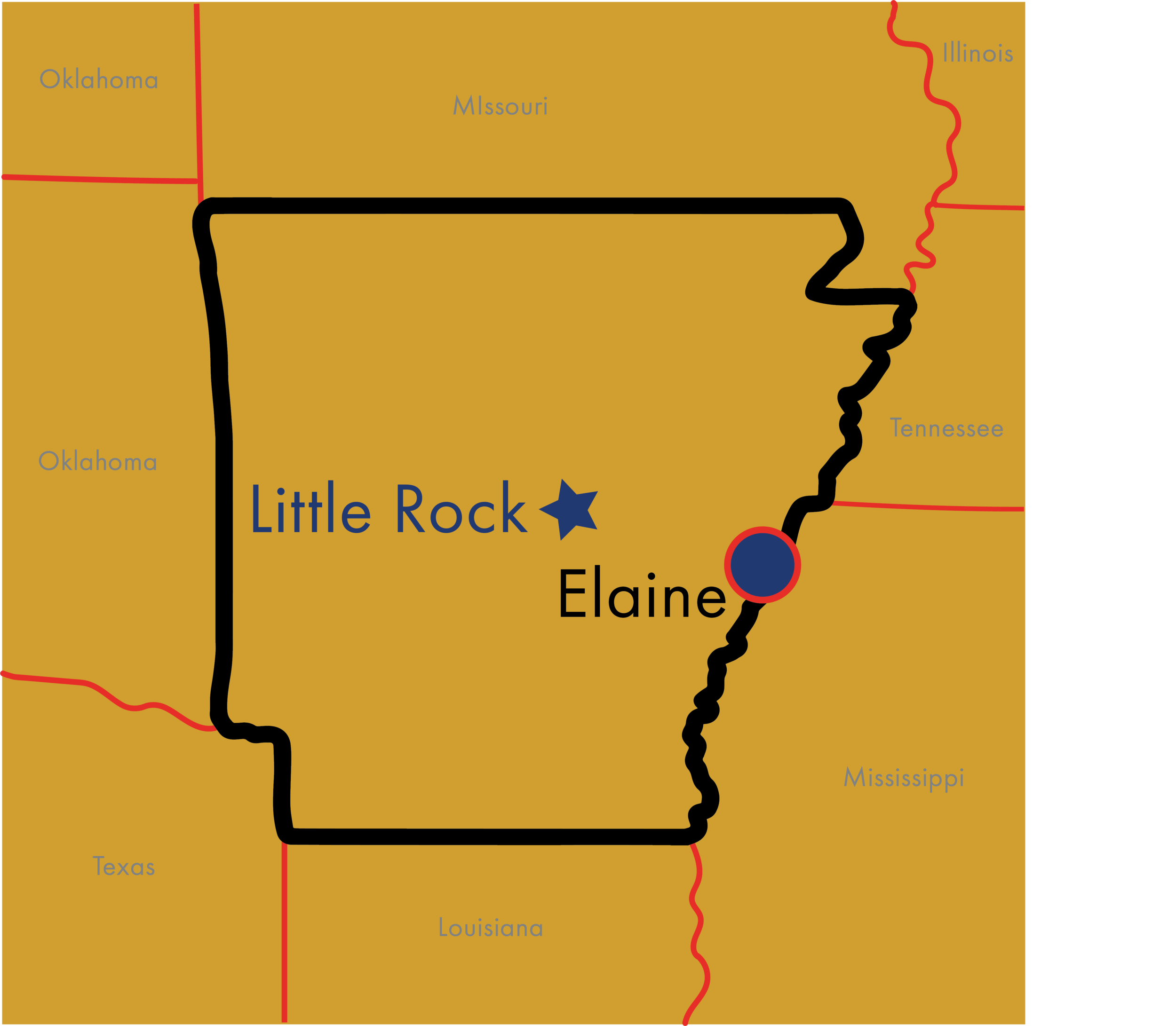

Elaine, AR, is an Arkansas village nestled in the Mississippi River’s rich alluvial soils of South Phillips County. The River is the boundary with the state of Mississippi. Elaine is so deep in the heart of America’s richest farmland that “the only way out is to turn around and return from where you came.” Over three quarters of Phillips County residents were African Americans in 1919 because federal land grant acts offered land ownership, and after the Civil War, the state developed a reputation as a land of opportunity for African Americans to farm and raise families.

By dark of night on September 30, 1919, several hundred Black Phillips County residents met in a local church near Elaine, Arkansas. Local Black farmers met to discuss joining to Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America to organize for better wages and working conditions from the surrounding landowners. Academics and media often write of “sharecroppers and tenant farmers” at this meeting as the genesis of the massacre, but threats to Black landownership and economic autonomy were already a rising threat.

One Elaine resident who was there that night, and would later be sentenced to death for false charges, John Martin, told Ida B. Wells-Barnett in an interview, “These white people know they started this trouble. The Union was only a blind. We were threatened before the union was there to make us leave our crops.” The dominant narrative describes the meeting attendees assembling in secret with two armed guards posted in front of the church for protection. The full details are unknown, but a small group of men approached the meeting, including a white deputy sheriff and white security agent from the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and a gunfight broke out. The shootout left the security officer dead and the deputy sheriff wounded. The rest of the party returned to Helena to spread the news of a "Negro insurrection".

By the morning of October 1, an enraged mob of up to 800 white men, from neighboring counties and states, began to descend on Phillips County to hunt down the purported killers and snuff out the supposed "Negro uprising". While many Black residents hid in the surrounding woods and fields, the white mob destroyed homes and businesses in Elaine and attacked, mutilated, and killed many Black residents. Under the orders of Arkansas Governor Charles Brough, and with the approval of President Woodrow Wilson's Secretary of War, Newton Baker, 600 federal soldiers were sent in to further quell the "insurrection". The commanding officer, operating on the accounts of white residents, ordered troops to "“kill any negro who refuses to surrender immediately.”

Estimates of the number of people murdered range from a few hundred to thousands, with the federal troops responsible for the majority of deaths. Oral histories of mass graves and undocumented burials would put the number much higher. As the violence was settled, over 200 Black people were jailed and 122 were charged with a range of crimes, including inciting violence. No white perpetrators were charged or prosecuted. Ultimately, 12 Black residents were given death sentences, which were eventually overturned thanks to the efforts of local African American lawyer Scipio Africanus Jones and the NAACP.

This makes the Elaine Massacre the deadliest act of racial violence in US history, according to some estimates.

“We used to own land but ...” is the common theme in oral histories descendants of the Elaine Massacre. At the turn of the 20th century, Arkansas had some of the highest Black land ownership in the US, and many descendants have memories of family ownership. However, during the chaos and dispossession in the wake of the massacre, many families lost their land under questionable circumstances. Today, documentation of land titles in Elaine remains scarce, but efforts are underway with the Elaine Legacy Center to search through archives to track that information.

The legacy of the Elaine Massacre had rippling impacts for the future Civil Rights movement. The lawsuit that arose out of the trials of the “Elaine 12” - Dempsey v. Moore - went all the way to the Supreme Court. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the 6-2 decision in the final case. Whereas previously, the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment left states as the ultimate arbiters and protectors of individual civil rights, the ruling in Dempsey v. Moore laid the groundwork for the expanded application of equal protection, noting that it was up to the federal courts to assure individual civil liberties. This case set the ball rolling for many cases that advanced the Civil Rights movements, including Brown v. Board of Education.

Reparatory Efforts in Elaine Today

Today, the Elaine Legacy Center (ELC) keeps the memory of the Elaine Massacre alive, and researchers at regional universities are beginning efforts to identify mass graves that have been lost to time. Still, Elaine struggles with the legacy of white supremacy. In 2019, on the 100th Anniversary of the massacre, the Elaine Legacy Center planted a tree to memorialize the event. The tree was soon chopped down and the memorial marker stolen. A memorial sculpture to the victims of the Elaine Massacre was erected in the County seat, Helena, but to Elaine residents, it felt "like a slap in the face", according to Elaine Legacy Center director, James White. Outside of the efforts of the center, no marker exists in Elaine.

Much of the story of the Elaine Massacre remains alive in the descendants still living in Elaine, today. Passing down oral histories is an act of resistance and preservation in the face of cultural erasure. In some significant ways, the oral histories of descendants diverge from the popular narratives that have been perpetuated over time. “The stories of descendants are of farm families who value the interweaving, sacred tapestry passed to them from their elders: God, family, community, and land.”

The descendants of this massacre are demanding justice in memory of their ancestors. NAARC is committed to working with families in this community to erect an appropriate memorial to this horrific crime, provide resources for an educational/public awareness program about the massacre, and support the righteous effort to receive reparations. Contributions from FFRN! will be held in escrow by NAARC and distributed in lump sums to fund ELC’s reparative justice projects.

Support for Healing from the Elaine Massacre of 1919

Following the leadership of the Elaine Legacy Center, the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference (SDPC), the National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC), and a growing network of local educational and religious institutions, the Fund for Reparations NOW! will direct our first rounds of reparatory contributions to support the creation of a permanent and long overdue memorial and museum to honor the lives of the African American residents murdered in the 1919 Elaine, AR, Race Massacre.

**In December 2020, FFRN! and NAARC sent a first reparatory payment of $50,000 to the Elaine Legacy Center!**

Reparatory Funding Goal: $50,000/$150,000

We are continuing to raise funds to support the Elaine Legacy Center’s reparatory efforts. Please join us by contributing HERE.

Partnership Timeline

June 2020: FFRN! a the request of NAARC and the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference (SDPC), began exploring ways to partner with and support the Elaine Legacy Center (ELC)

September 2020: Beginning of formal partnership with ELC, including regular digital meetings and check-ins

December 2020: First reparatory payment of $50,000

Future: Look forward to digital events, educational campaigns, and more!

Learn More About the Elaine Massacre

Visit the Elaine Legacy Center’s Youtube Channel to find videos from past events featuring Elaine descendants, and you can learn more about the untold story of the Elaine Massacre by watching this documentary produced with the people of Elaine by our partner, the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference.